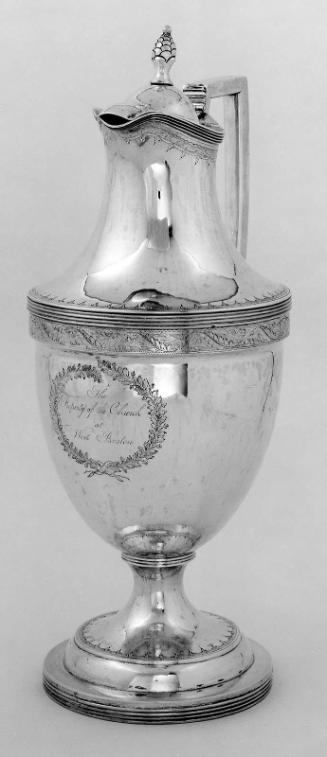

Bowl

Virginia Wireman Cute (fig. 1) represents the old and the new in the world of American silversmithing. She is the daughter of illustrator Katharine Richardson Wireman (1878 – 1966) and a descendant of Francis Richardson (1681 – 1729), a colonial Philadelphia silversmith. Cute reinvigorated the city’s reputation for fine craftsmanship when she was appointed director of silversmithing and jewelry at the Museum School of Art, now the University of the Arts. As evidence of her energy and enthusiasm, enrollment in her department rose from 20 pupils in 1942, the year of her appointment, to 175 in 1950.2

Cute pursued two parallel and sometimes interconnected careers. Her first degree in 1929 was earned from the Philadelphia School of Occupational Therapy (University of Pennsylvania School of Auxiliary Medical Services). From 1931 to 1935, she continued her studies at the Philadelphia School of Art and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from the Moore Institute of Art. About the time of her appointment to the Museum School, she studied briefly in New York with Swedish-born silversmith Adda Husted Anderson (w. in the United States about 1930, d. 1990) and with Walter Rhodes (1896 – 1968), probably at the Crafts Students League.

Cute’s skills were honed at the 1947 Handy and Harman silversmithing conference run by Margret Craver, which reintroduced traditional hollowware-making skills to a new generation of American art students (figs. 2 – 3). William E. Bennett, professor of the Sheffield College of Arts and Crafts in England, taught the 1947 session. Upon her return to Philadelphia, she urged Richard Reinhardt (1921 – 1998), a Museum graduate and professor, to attend; he succeeded her as head of the department.

In 1949 Bennett invited Cute to study with him in England. While there, she became the first American woman whose touchmark was accepted into London’s Goldsmiths’ Hall. She traveled in 1953 to meet Baron Erik Fleming, silversmith to the Swedish court, and Count Sigvard Bernadotte (1907 – 2002), brother of the queen of Denmark and designer for Georg Jensen, the Sheffield College of Art, and the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths. One of her travel companions was Phoebe Phillips Prime (Mrs. Alfred Coxe Prime), an antiquarian and silver specialist. Throughout this period, Cute lectured, exhibited, and published in the field of American silver.

In 1953 Cute returned to her earlier field to become assistant director of the Philadelphia School of Occupational Therapy. She remained with the department until the early 1980s.

This sleek bowl, with its low, almost space-age profile, was made in a manner taught at the Handy and Harman conferences. The technique of using a graver to insert small “stitches” underneath the bowl to center the foot ring is carefully explained in a 1948 Handy and Harman instructional film and booklet entitled “Handwrought Silver.” Stylistically, the bowl adheres to the Scandinavian modern style that is found in the work of all conference participants. The entwined script monogram of the artist’s name, however, is a reminder of Cute’s colonial ancestry.

This text has been adapted from "Silver of the Americas, 1600-2000," edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward, published in 2008 by the MFA. Complete references can be found in that publication.