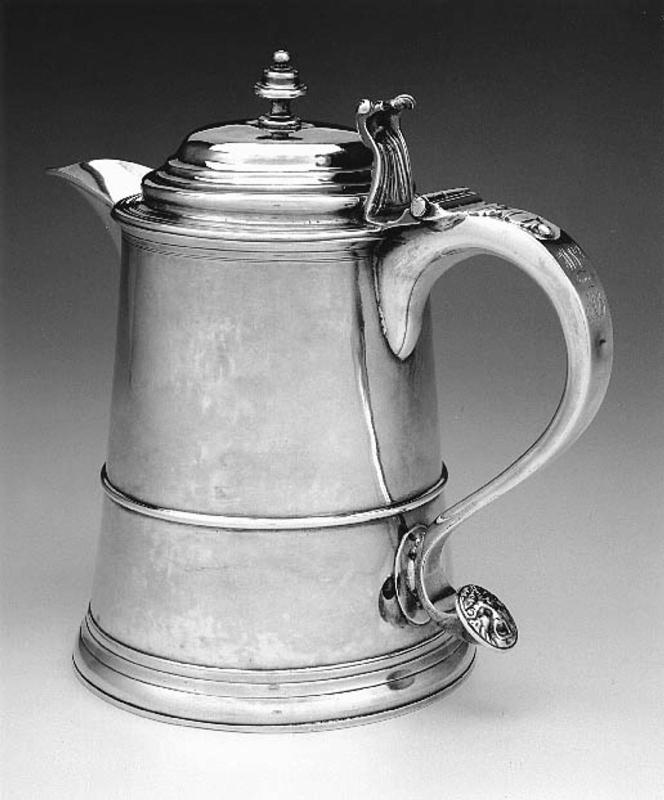

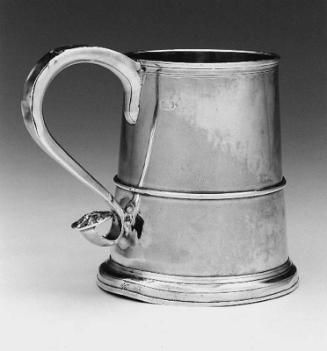

Tankard

This classic Boston tankard, with its tapering walls, low midband, domed lid, and grotesque terminal, is nearly identical to the previous Burt example (cat. no. 16) but is notable for the spout that it received sometime in the nineteenth century. The transformation of colonial-era tankards into pitchers has been commonly attributed to the influence of the temperance movement beginning in the mid-1820s. The first documented “spouting” of a tankard occurred as early as 1816, however, suggesting that a trend to adapt tankards to new uses was already under way by this date.

The tankard’s traditional use as a drinking form was likely dealt a deathblow by the temperance movement, but its morphology may have more to do with changing attitudes toward health, etiquette, and taste. Due to their size, most tankards were considered communal vessels to be shared among friends, family, and church. The cup as a symbol of fellowship, for instance, was a medieval convention born of necessity in an era with few individual drinking cups. As cheap imports and new American products made glass and ceramic drinking cups affordable to many Americans, private use or ownership of such vessels became a reality for those who previously made do with inexpensive treen or horn. An increasing awareness of good hygiene also led to the demise of shared vessels. Beginning in the mid-sixteenth century, it was understood that contagious diseases could be passed from one person to another. Personal etiquette gradually changed to reflect this concern, as books on manners of the period urged their readers to wipe their mouths before sharing in drink. Yet Americans in the late eighteenth century still retained the tradition of communal vessels. An American traveller in France decried the practices of his countrymen, which risked the contraction of disease, and noted that in France, “every man has his own glass, and risks no one’s lips but his own.”

The Museum of Fine Arts has some spouted tankards in the permanent collection, along with others that were “de-spouted” in the twentieth century by owners who wished to return the vessels to their original form. The residual engraving on the body opposite the handle suggests that this tankard may have sacrificed a coat of arms to the new spout.

As with pewter, untold numbers of silver hollowware and flatware pieces were regularly melted down and remade into newly fashionable works during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The spout was a frugal and efficient method of retaining an old-fashioned yet pleasant form while adapting it to new uses. For Americans who continued to purchase outmoded tankards and porringers until the end of the eighteenth century, improvisation on an old form was one manner of bridging cultural gaps, keeping the familiar at hand while bringing in the new.

This text has been adapted from "Silver of the Americas, 1600-2000," edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward, published in 2008 by the MFA. Complete references can be found in that publication.

[1] Thomas B. Wyman, Jr., "Pedigree of the Family of Boylston," NEHGR 7 (1853) 145-50; NEHGR 15 (1861): 364; Park, Gilbert Stuart, I:172-74, cat. 106-08; Mary Caroline Crawford, Famous Families of Massachusetts (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1930), p. 9-12; Stark, Loyalists of Massachusetts, pp. 281-83; Boston Newspapers 1:35.

[2] MFA paintings catalogue [old one] p. 129, cat. 475, fig. 206. painting by???

[3] Massachusetts Vital Records, Births, Vol 35, p. 66; Vol. 459, p. 551; Massachusetts Vital Records, Marriages, Vol 227, p. 341; 227, p. 341; Massachusetts Vital Records, Deaths 1847-1848 Vol 33, p. 205. Princeton, Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850, (CITY, PUB. DATE___________) p. 81, 151; Roxbury, Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850 (CITY, PUB. DATE___________) 1:36; 470-71; Obituary, Boston Herald, August 17, 1966;

Obituary, [Portland] Maine Press Herald, p. 2;