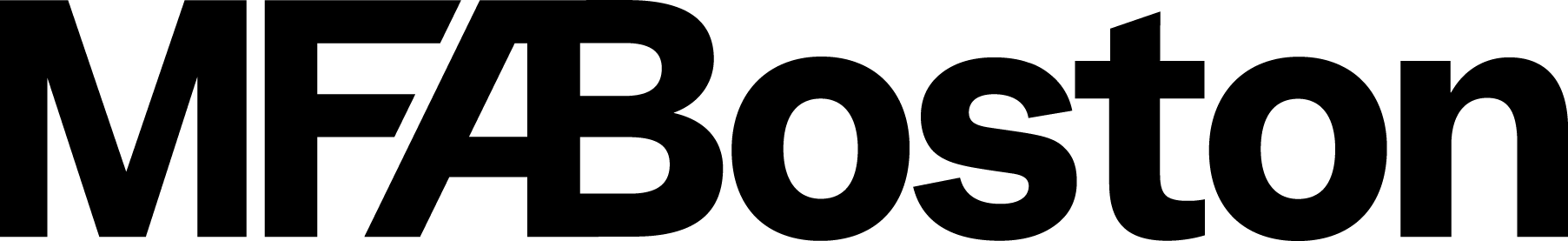

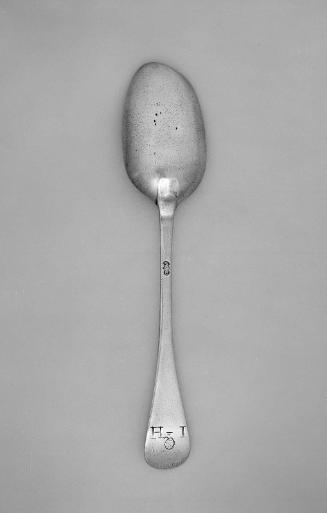

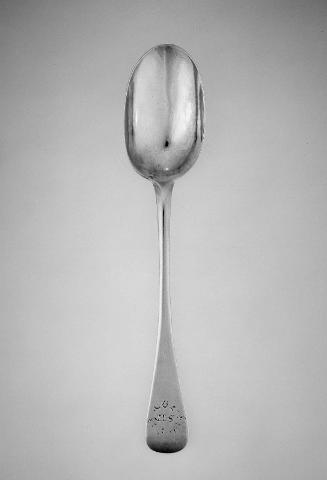

Marrow scoop

This slender but sturdy implement was a popular form in England and America since colonial times. This practical tool was developed sometime after the evolution of the marrow spoon, which has an ordinary bowl with a stem in the form of a narrow scoop. The uneven widths of the scoop offered the user an advantage when extracting protein-rich marrow from bones of different diameters once these were cooked and broken open.

Although marrow spoons and marrow scoops had been used in England as recently as this century, the utensil experienced a more narrow range of popularity beginning in the mid-eighteenth century. Aside from this example, several other mid- to late-eighteenth-century marrow utensils are known, including two from Massachusetts (one is by John Jackson [d. 1772] of Nantucket) and another with a stepped handle that was made by John Coburn. Examples by Hugh Wishart (about 1784 – 1819) and Charles Le Roux (1689 – 1748) have also survived, among New York makers. Two small revivals of the form took place. The first emerged in Connecticut at the beginning of the nineteenth century, with known examples by Charles Brewer (1778 – 1860) of Middletown and Joseph Church (1794 – 1876) of Hartford. The second occurred in Albany, New York, where Shepherd and Boyd produced marrow scoops notable for a lozenge design on the stem.

English marrow scoops and spoons were undoubtedly used in the colonies, as proved by an example dated 1764/65 by London silversmith Thomas Tolman that was recorded in the estate of Sally Pickman Dwight. Marrow scoops and spoons of unknown manufacture sometimes appeared in the public record. In a 1773 advertisement, silversmith William Whetcroft of Annapolis enumerated “soop-ladles and spoons, table, desert, marrow, and teaspoons” along with a mountain of domestic goods and and personal accessories, most of which were probably imported from England. It is probable that the “Silver Table, Marrow and Tea-spoons . . . from London,” offered in a 1784 South Carolina advertisement by Roger Fursdon, were also of foreign manufacture. In view of such advertisements and the scarcity of documented American pieces, many of these utensils were likely imported.

Few early New England – made marrow spoons are known. Aside from the Coburn and Jackson examples, Joseph Edwards Jr. made one in 1765 for Joshua Green, and Paul Revere II sold two pairs in 1785 and 1786 to miniature painter James Dunkelly (also spelled Dunckley), according to receipts and account records. Thus, the Hurd example is a rare surviving colonial New England version of this specialized utensil.

This text has been adapted from "Silver of the Americas, 1600-2000," edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward, published in 2008 by the MFA. Complete references can be found in that publication.