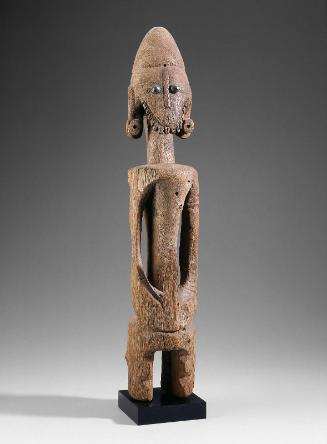

Reliquary figure (mbulu ngulu)

The face of this Kota reliquary guardian would have glimmered inside a dimly lit room. The smaller sculpture’s face is highly abstracted, with the eyes and nose centered on wide strips of glowing bronze. Bronze wire, hammered into narrow strips, decorates the rest of the shallow dish that forms the face. One of only nine known figures by the Master of the Sébé, this sculpture was made in Gabon in the eighteenth century. The sculpture has a delicate, diminutive appearance to evoke the face of a younger woman. It would have originally been seen as part of a group of three, along with a senior woman and a man. The smooth semicircles on the top and sides of the head represent the figure’s hair, and the small spools on either side are earrings. The lower half of the diamond-shaped support would have been placed inside a reliquary basket, not exposed as they are today.

Together, a group of three reliquary guardians—male, senior female, and junior female—represented ideal ancestors whose relics were held in a basket below. Kota communities moved every few years, when the quality of the soil could no longer guarantee abundant crops. Reliquary baskets, like the one these figures would have ornamented, helped families maintain a memorial to their beloved deceased relatives when they moved to a new place. The Kota converted to Christianity beginning in 1900, and reliquaries were no longer kept. Communities abandoned their reliquary figures or destroyed them as proof of their new faith, often pressured by missionaries. Local traders and colonial officials—at times even the missionaries who had encouraged the sculptures’ destruction—then sold the cast-off reliquary guardians in Europe.