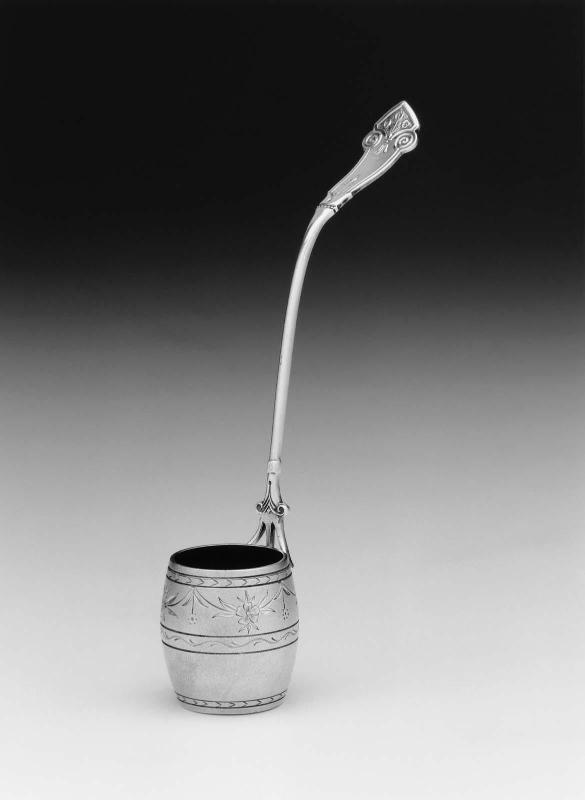

Ladle with barrel bowl

Perhaps intended for serving cream or another rich liquid, this small, whimsical, barrel-shaped ladle fits snugly into its own satin-lined case for safe keeping. The handle pattern with Neo-Grec-style spirals is similar to others produced about 1870.

Early in his career, Newell Harding manufactured the well-known fiddle- and olive-patterned spoons made by many other manufacturers. In 1841 Henry L. Webster, a Providence, Rhode Island, spoonmaker, joined Harding’s firm. After an apprenticeship in Boston, Webster had returned to his native Providence to become Jabez Gorham’s first partner in a spoon manufacturing business. In 1841 Webster sold his share to Gorham and returned to Boston, where he was associated with Harding until 1851, the year Harding took his sons into his business and renamed the firm Newell Harding & Co. Webster returned to Providence after this date and formed a new silver flatware manufacturing company.

In the 1850s Lewis Kimball, another spoonmaker, joined Harding’s firm. He remained until 1863, leaving soon after Newell Harding Sr.’s death in 1862. He remained in business for himself in Boston, producing “for the trade and to special order, both plain or the most elaborately ornamental silver spoons, knives, forks, ladles, etc., of his own or special designs furnished by his customers.”

The firm may have always retailed some wares by other makers. Yet, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish between the firm’s manufacturing and retailing roles after Harding’s death in 1862 and the departure of Kimball in 1863. The majority of flatware marked by Newell Harding and Newell Harding & Co. in the Museum’s collection bears no other marks. However, a large ladle in the Prince Albert pattern in a private collection bears the marks of Newell Harding & Co. and Michael Gibney of New York, who patented the Prince Albert pattern in the 1850s. A jelly spoon (1999.64.6) in the Museum’s collection bears only Harding & Co.’s mark but is identical to Knowles & Ladd’s Emperor pattern, which was introduced in the early 1870s.

R. G. Dun & Co.’s last report on the firm in 1866 remained gloomy: “not much to them, drink too much” (see cat. no. 203). Nevertheless, Newell Harding & Co. remained in business until 1889, perhaps due to the solid reputation built by its founder during his long career.

This text has been adapted from "Silver of the Americas, 1600-2000," edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward, published in 2008 by the MFA. Complete references can be found in that publication.