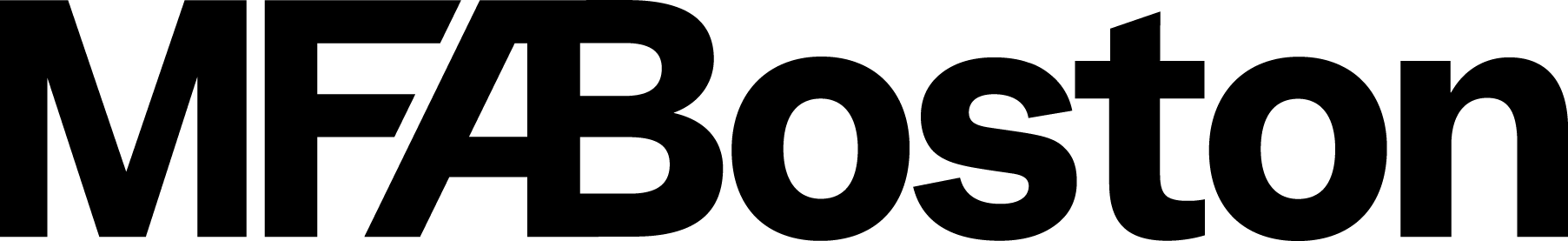

Chocolate Pot

Chocolate pots, like sugar boxes, were among the rarest silver forms in the early eighteenth century. Fashioned for an elite clientele to serve imported luxury foodstuffs from the Caribbean and its southern neighbors, many of these vessels were lavishly decorated in the international Baroque style.

The desire for such fine goods came from wealthy local merchants and a succession of royal appointees from abroad who had sufficient funds and an appetite for the latest styles. For instance, while stationed in New England between 1708 and 1709, Scottish captain Walter Riddell purchased a large unadorned punch bowl from John Coney in the newly fashionable Georgian style (cat. no. 32). Many recently arrived craftsmen served as transmitters of the latest trends while working as journeymen for established Boston artisans. They enabled the city’s workshops to deliver goods in current London fashions for discriminating patrons and, ultimately, through diffusion to the general population.

Such objects offer a useful corrective to the modern image of an unrelentingly dour Puritan existence. More than a few colonists showed an inclination for personal adornment despite religious teachings against vanity. They dressed in handsome clothes and decorated their homes according to their means. Only a few could afford the elaborately worked surfaces of sugar boxes and chocolate pots. The commanding sculptural presence of these forms and the rare commodities they held provide us with a perspective on the tastes and culture of an assuredly small but very cosmopolitan group.

London-trained silversmith Edward Webb was an active member of the craftsman community, arriving in Boston after 1704. More than forty examples bearing his mark have survived — a large group considering that Webb’s career in Massachusetts lasted only about fourteen years, until his death in 1718. Most of his silver is undecorated, perhaps to suit the majority of his colonial customers, but the impressive range of tools recorded in an inventory of his estate proves that he was well equipped to create forms such as those he crafted as an apprentice in the London shop of William Denny (active 1679 – d. 1709). This chocolate pot, a recent discovery, is stylistically closest (presumably) to the silver he fashioned in England, and it is unarguably his masterpiece.

Of the eight chocolate pots by five Boston silversmiths that have survived, six were made before 1720. Of these, four are distinguished by a tall domed lid and ribbed or fluted decoration derived from English precedent. The group of four includes this example by Webb; one made by Peter Oliver (about 1682 – 1712), possibly for Beulah (Jacquett) Coates; and two by Edward Winslow, who fashioned one vessel for the Auchmuty family and the other for merchant Thomas Hutchinson. Stylistically, this group is as advanced as any created abroad.

Webb differed from Winslow and Oliver in his method of creating the broad bands of vertical decoration seen on this vessel. Following the practice of Denny’s shop, Webb flat-chased the narrow concave or fluted channels, rather than taking the extra time to fashion reeds, which involved repoussé work as well as chasing. Webb’s narrow irregular flutes, with their erratic punctuated borders, were characteristic of silver from Denny’s shop, as can be seen in a monteith dated 1702 and a mug from 1703, both ostensibly made before Webb’s departure for Boston. This distinctive treatment points to Webb as a likely journeyman for John Coney, whose monteith for Boston merchant John Coleman has fluted sides and a contrasting gadrooned foot similar to those seen here.

Aside from the mildly stimulating medicinal properties attributed to chocolate, it was considered a relaxing social drink. Dissolved in a solution of claret, milk, egg, sugar, and spices, and stirred with a rod or paddle inserted through the lid, chocolate was prepared slowly, which no doubt contributed to the ceremony and enjoyment of the beverage. An export of provinces belonging to Catholic Spain, chocolate may have offered a brief mental escape from reformist strictures. Often set against a background of “studied leisure,” the luxury of chocolate drinking may have fallen out of fashion among the wealthy, who found the connotations of idleness and even licentiousness to be not in keeping with their Protestant upbringing.

The popularity of chocolate never matched that of tea or coffee, this last being politically preferable to tea during the Revolutionary War. However, its consumption perhaps should not be judged according to the survival of chocolate pots, for these specialized forms may have proved too expensive for many households. Julie Emerson notes that coffeepots and chocolate pots were “interchangeable” in Europe, and perhaps in the colonies the same proved true. The need for stirring rods (molinets) to dissolve the chocolate may have been rendered less necessary with the availability of improved grinding methods, as advertised in 1737 by an unnamed Salem gentleman. Still, only two Boston silver chocolate pots dated after 1750 are known, both made by Zachariah Brigden. The presence of two chocolate grinders in the Boston directory of 1789 proves that the market for the beverage, if not the form itself, continued through the end of the eighteenth century.

This text has been adapted from "Silver of the Americas, 1600-2000," edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward, published in 2008 by the MFA. Complete references can be found in that publication.